Gunther Gerzso

80th Birthday Show

|

|

|

Gunther Gerzso

Dore Ashton

|

|

| page 1 | page 2 | page 3 | page 4 |

|

|

I think Traba

was right to see landscape as the central motif in Gerzso's life's work, and

specifically, the Mexican landscape. His work as set designer for over two

hundred Mexican films brought him to survey the entire country with an eye

to wresting from the panorama a telling abstraction. Yet, this is a landscape

of the mind, through which flows so many elements, not the least, the human

image. Metamorphosis, another Surrealist value raised to the highest degree,

plays its part in each of Gerzso's paintings. So do ambiguities, and secrets,

that all writers on his work have felt reside behind the hard, luminous

picture plane. Take only one of his paintings and linger with it: Landscape,

Orange-Green-Blue of 1982.

We are confronted with a vast but bounded field

of orange (not entirely opaque however-there are yellow and ocher undertones

and flecks of ocher making the final plane vibrate). This field is, as are many

fields in Gerzso's paintings, not only a field but a wall and also a curtain as

might exist on the stage of an avant-garde drama. Within the field are four

unattached lines, each with a nimbus, each as frail as a comma, and each

providing the painting with a different scale. Now scale, as every painter

knows, is a difficult problem. It is not just a matter of large and small. It

must incur mysterious relationships. Klee never spoke of scale in itself.

Rather, he spoke of "measuring and weighing." One can measure and weigh the

plane of orange only as one measures the weightlessness of these threads of

line. And temporality, as Klee insisted, enters. The time the eye takes to

scan the plane is measured in terms of the fragile commencement in the line.

In this painting, as in many other recent paintings, Gerzso has again invoked

the special qualities of line which can at once describe the final boundary of

a form and suggest the life of the form behind. The shaded line, the swelling

line, the diminishing line, the hairfine line serve him both to illuminate the

character of his planar forms and to suggest mystery and depth. A pair of

blue bars, overriding the orange plane in this painting are separated from it

by delicate dark lines. These two blue bars, as musical as any of Klee's, set

off another set of juxtapositions, and another, as the

horizontal planes pass into infinity.

But it is not only a matter of the

surprising juxtaposition of planes in different scales. Here, and I think in

most of Gerzso's paintings, there is a specific surreal emphasis. The three

dappled blue shapes, roughly rectangular, that ride on the very surface of the

painting, are, in fact, windows, and the cool blue is nothing other than a

Magritte-like allusion to sky. Glass, reflection, sky, boundaries, houses,

inside, outside-how many associations does he not compress in this intense

abstract painting by means of these unexpected illusions of the real. The

cracked, window-like shape has existed in many of Gerzso's paintings,

including works as long ago as 1965, and can be compared to other shapes in

his paintings in which there is a deliberate, slashing rent-symbol of broken

idols, shattered monuments, archaic memories of separation and even death.

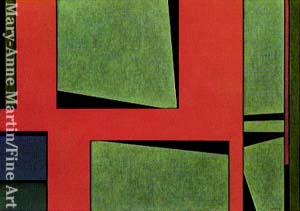

23. Naranja-azul-verde, 1972

|

There are paintings that Gerzso has titled to refer us to the association with

ancient Mexico, and others where the shapes, so firmly trapezoidal or

rectilinear, inevitably evoke the architecture of the Mayans or the Aztecs.

But there are others in which he gives us the clue to the reading that he calls

"personage-landscape" (in Spanish it has its implicit poetic elision:

personaje-paisaje). These are paintings in which the personage, as would a

character in the theater, is all but hidden behind the coulisses. It is a

presence. It exists in a vertical clatter of planar infinity, or on the vast

plateau of Mexico, but always reticent, always masked. This personage is

certainly Gerzso, who has diffused himself throughout his paintings, with

only a few, but very telling clues to his physical being as a man. The process

of masking; of layering memory (does he not call one of his paintings Ancient

Abode, and suggest the living presence of himself and all others?) is carried

out with a painter's rigor. Each plane secretes another. Each color makes

another shine. Each line has its opposite. Everything in the world is firmly

compressed. And behind, the vivid presence of the eye that discerns, that

extends. Gerzso is certainly Gerzso and nothing else.

|

|

|