Elena Climent

Re-encounters

|

|

|

Ordering Objects:

Acts of Time

Sarah M. Lowe

|

|

| | page 1 | page 2 | |

|

Elena Climent's

delicate, evocative still lifes - pictures of accumulated

objects she painstakingly collects, arranges and reproduces - may be seen as

performances, that is, as representations of the act of ordering. Climent is

exceptionally deliberate about precisely what objects appear in her work,

despite the seemingly vast array of things that populate her canvases. Her

willful selection is the subject of her art: vases, candles, books, dolls,

plants, birds, fruit, keys, photographs, letters, and the detritus of everyday

life at the end of the twentieth century, all hold meaning for the artist.

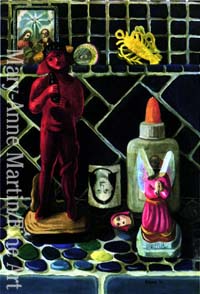

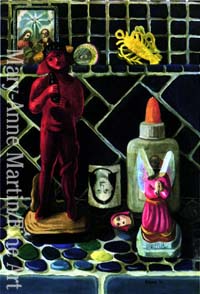

10. Red Devil with Broken Angel, 1994

|

For Climent, her paintings "symbolize feelings through objects" and she thinks of

them as stories, and although the viewer is not

necessarily cognizant of the specific narrative she has in mind, the intense

realism of her formal style and the sheer accumulation of "facts" are

riveting. We scrutinize these dazzling, detailed, and tightly painted still

lifes for clues, messages, meanings. The evocation of the mystical in works

such as Red Devil with Broken Angel and Catalogue of Bosch, as well as their

small size, reveals their lineage from the MexiIcan ex-voto. A paraphrase of Diego

Rivera's observation regarding the subject matter of the retablo is

eminently applicable to Climent's work: miraculous events are made ordinary

and everyday things are turned into miracles.

Climent is motivated by the

acute knowledge that things from her past have been lost to her, and that

through the act of reproducing her inheritance she can claim it for herself.

Never far from her mind is the idea of heritage, of coming to terms with who

she is. This decidedly Mexican pre-occupation is evident especially in the

vanguard movements in the early part of this century. In rejecting European

influences, the artists of the Mexican mural movement

and the Estridentistas (Mexico's answer to the Futurists) self-consciously

sought to advance a specifically Mexican art, and in so doing, they honored

the multi-racial ancestry that is the heritage of virtually all Mexicans.

Climent's search is not quite as literal as that of her Mexican progenitors.

Rather, her paintings now emanate the poignancy of the expatriate, in part

because she is no longer living in Mexico where she was born and raised, the

daughter of two exiles (her mother was an American Jew and her father a

Spanish liberal). After six years of living in New York City, there are

noticeable if subtle changes in Climent's work. Mexican middle-class

household scenes of a family's altar with a tattered reproduction of the

Virgin of Guadalupe or a kitchen shelf stacked with packaged foods were

predominant in her work before leaving Mexico. Unequivocally antifolkloric,

her pictures were, nevertheless, reminders of her childhood and were

steeped in a nostalgia for a past at odds with the standards of "good taste"

which was part of her upbringing and which she was expected to uphold. Once

abroad, Climent continued this theme, painting from photographs she had

taken during visits home. Often she copied a casual snapshot completely or

took it as a setting to structure items she imported from Mexico such as

votive candles and brightly colored plastic tablecloths.

|

| continued |

|

|