Elena Climent

In Search of the Present

|

|

|

In Search of the Present

Elena Climent

|

|

| | page 1 | page 2 |

page 3 | page 4 | page 5 |

|

|

My

mother was also worried about the fact that we were growing up without an

identity. She couldn't raise us Jewish or Catholic with my father, who

despised any institutionalized belief. He was of Catholic origins, but after

his father's efforts to turn him into a priest, he turned out an atheist and

would have been a declared anarchist if he weren't so much against being

called anything. When asked about his nationality or religion he would

declare himself to be a mammal, and refuse to specify any further.

So here

we were, the three daughters of two people who came from completely

different backgrounds, trying to decide what we were supposed to be. The

only thing that was clear was that we were Mexican, because we had been

born in Mexico and were being raised there, and to this both of our parents

agreed.

Being Mexican became very important to us, and we took to this with

the determination of a convert. Sometimes when you

aren't quite in the middle of things you have a better perception of your

environment and a greater capacity to appreciate it, and this was certainly

our case.

But we weren't Mexican like our Mexican neighbors, we were

Mexicans who could see things from the outside. Because our home was

different from the other homes, and our parents didn't think like the others.

They were constantly transgressing social rules and we, as children, were

very sensitive to the tensions this caused. I think that this is part of the

reason why we became so aware of the codes of behavior around people who

surrounded us and learned to deal with them with great ability.

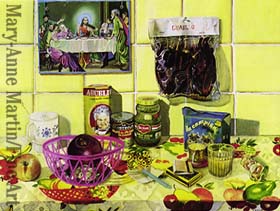

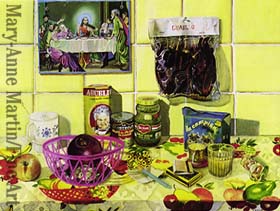

Yellow Kitchen, 1991

|

We didn't

belong to a social class, and at the same time had access to all of them,

from the very rich, to the very poor. We could feel quite comfortable in any

home and knew just how we were supposed to behave in each one of them.

But what we were and where we belonged was not clear. As a matter of fact,

we were many things at once: the poor people who lived on the north side of

our neighborhood accused us of being rich, white and foreign. To our

neighbors from the other side (Mexican conservative upper-middle class

Catholics) we were bohemians and Jewish. In the American School, where my

mother sent us in spite of my father's complaints, we were poor and Mexican,

and had to deal with conflicts that would even lead to violent fights. It was

only in the circles of my parents' friends that we were just normal and could

feel comfortable. But it was a world that had little future for us, the

younger ones. It was based on shared nostalgias, dreams, a taste for

wonderful environments that were representations of these dreams of old

times, real or not real. It was wonderful. All these homes we visited, where

we would all gather for parties, or 'happenings,' as I later called them, were

recreations of a perfect world that everyone believed to have existed at

some point in their memories. Beauty as seen from a classic point of view;

objects carefully organized, matching colors, harmony, composition,

symmetry, the light coming in through a certain window at a particular time

of day, hitting right on a specific corner of the room in such a way that

would remind you of a painting, perhaps a Rembrandt. The background music,

the lit fireplace as the heart of everything, someone sitting next to a lamp,

drawing. Maybe someone would read a poem, perhaps a musician would

entertain us with his music, a friend who could cook would prepare a very

special meal for the occasion.

|

| continued |

|

|