The first issue of Margins, all 6 legal sized sheets of it, with

a single staple in the upper left corner, came forth from Tom Montag's

apartment on Bremen Street, Milwaukee, in August 1972. Dave Buege acted as

co-editor, and Morgan Gibson and Marty Rosenblum acted as advisors.

Instead of joining the lists of magazines that published poetry, theirs

would concentrate on reviews and related criticism and commentary.

The orientation was largely toward the kind of regional poetry to which Montag

has since returned. That may have held a center of balance had Tom not

been sincerely interested in what other people had to say. Although

regionalism per se holds no interest for me, part of his midwesternness

is the same kind that I still find essential and laudable: thoroughly

pluralistic, and not much interested in hierarchies that didn't

prove themselves. To me this has more to do with my residence and

association with the midwest than the industries from which I learned a

great deal or the landscape which I love or the history I admire or

the Mound Building Native Americans who have fascinated me

since childhood or the farms which remain largely unfamiliar to me.

I liked the neighborhood in which Tom lived, having moved out of it shortly

before he moved in. Tom was completely friendly, without pretensions,

and interested in anything that I had to say that had the potential of

making sense to him. He had started publishing broadsides under Morgan

Gibson's tireless encouragement. He had a tiny hand press designed to

produce business cards, which he started trying to print with. He thought

I could help him with it, though there's not much but business and greeting

cards you can do with this kind of press - even if you have more expertise

than I.

I felt skeptical about Margins when its first issue

came out, but contributed several reviews to the third, and am listed

with Marty Rosenblum as Contributing Editor in issue 4. In this period, I

don't know whom Tom listened to most, or how much he was influenced by

the changes from mimeo to offset which had caused a rapid expansion in

alternative publishing. By issue 4, the tone of the magazine

was no longer bucolic or regional in outlook, though such orientation

was not altogether missing. This was the essence of the way the magazine

worked during the next years. Tom and the other original staff brought

other people into the magazine, and Tom expanded it according to their

interests and his. Although the staff grew through associations, there

was nothing homogeneous about its members. None completely agreed with

any other, several felt antagonistic, and there was never a single

occasion when the whole staff assembled in one place at the same time.

Degrees of participation and contribution varied: I brought Richard

Kostelanetz in, for instance, and he did little but supply Tom with copy

of his own each month. Others carved out autonomous zones within the

magazine. Tom did little to discourage this, even at times when those

turfs caused contention. On such occasions, Tom's attitude was not to

conciliate or look for compromises, but simply to duck the squabble and

go with whatever both parties wanted to do. This strategy takes

a lot of skill and some dissembling, but Tom was a master at it, and

it may be the most salutary aspect of his editorship.

Tom also had a strong ability to learn what he was doing as he went

along. Given his agility, flexibility, lack of biases, and unwillingness

to feel belittled by the accomplishments of others, he could pick up

new ideas from the wildly diverse group of people around him, and make them

his own in his poems and criticism. This faltered near the end of the

magazine's life, but during it's heyday, Tom was a model of what a

poet, critic, and editor could allow himself to be. I haven't seen an

editor like him since.

The magazine grew rapidly in size and keeping it going came to require

an elaborate support structure. Tom's wife Mary was willing to finance

her husband's efforts by working as a nurse. This was not an unusual

situation in literary or political circles, but Mary's family moved the

oddness of the situation and the moment in American culture into hyperspace.

Her father was a professor of Botany at the University of Wisconsin, and

her mother was not only a Professor of English Lit, but also the chair

of the department during a good deal of the magazine's existence. They

lived in a large house near Lake Michigan that at one time had been the

preserve of those near the top of the financial heap - people who had

servants and large houses, but could not quite afford the mansions a few

blocks east on the lake shore. As Tom's involvement in Margin grew, his

parents-in-law, Kay and Phil Whitford, invited them to live in one set

of servants' quarters in the house. These "quarters" were more comfortable

and spacious than the apartments of many staff members. For a brief

period Marty Rosenblum and his wife occupied a subsidiary set of

servants' quarters without getting in the way of the elder Whitfords,

the Montags, and Mary's brother, who also had rooms in the house.

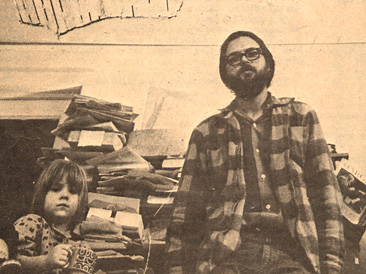

Tom converted most of the basement into offices. Here

he could not only work on the magazine, but also look after his first

daughter, Jennifer, and the second, Jessica, who was born while the

magazine was in operation. With children present, there was a television

constantly on in one of the office rooms. I carried an armada of colored

pens in my shirt pocket, along with such tools as a miniature flashlight,

ruler, magnet for fishing things out of my press, and so on. During most

of my conversations with Tom - some of which went on for six or seven

hours - Jessica sat on my lap and drew pictures, sometimes with me making

suggestions, putting balloons and speeches in characters' mouths or adding

other details. I like kids, and liked the family orientation

of the offices. I don't know how some of the other staff members managed

kids on their laps and blaring television in the background. I did after

all believe in cottage industries and integrated communities, and this

one seemed like part of my "federation," though Tom and I didn't talk

much about that kind of politics.

Others had axes to grind. We thus had

the situation where the basement supported a constant flow of editors

who ranted and raged about the evils of the privileged classes, the

degeneracy of academe, the scummines of "straights," the need to destroy

the nuclear family, and so on and on in the basement of a former

mansion owned by two well-heeled professors, who personally and

financially supported their son-in-law's ever-growing, never-paying

magazine. I found it absolutely delightful that Kay and Phil not only

supported this, but actually found the downstairs zoo interesting. Kay

at times became directly involved with reviews of reprints of labor and

feminist lit from earlier eras, particularly the 1930s.

Important to me, and in character with

the informality of the house, they left the back door open or a key out

for me at night so I could come in at, say midnight, and set type for

my books until perhaps three in the morning. While doing this, I might

hear Kay and Phil listening to an opera recording just as I came in, and,

more faintly, an old movie from Tom and Mary's rooms after the elder

Whitfords had gone to sleep.

By the beginning of 1974, Margins was unquestionably the most

important review journal for alternative literary presses in the country.

Review copies poured in by the hundreds. Poets from around the world

came to visit. One of the indicators of the magazine's importance that

amused me most was that during my annual pilgrimages to New York, I may

have been treated graciously by the tribal elders, but people my own

age invariably tried to brow-beat me into reviewing them or getting them

onto the staff - as often as not telling me that I needed to move to

NYC in between salvos on what I was supposed to do for them back in

Milwaukee.

Although not too many people like to give the magazine its

due credit now, a lot of prominent poets got essential reviews and

opportunities to write and to make contact with others through the

magazine. As a sort of bench mark, I like to point to Hannah Weiner:

I commissioned the first, and virtually the only, essay she wrote, and

arranged for Dick Higgins to publish the first review

of anything of hers ever published - both for Margins. That seems

emblematic enough. Another signature comes from two magazines which

came in to take the place of Margins shortly after it folded.

American Book Review took over the more reserved functions

of the magazine, while Fact Sheet Five took off from its more

egalitarian and comprehensive characteristics. I don't know if these zines

owed much directly to Margins, but I think it's safe to

say that they would have not been the same had Margins not

preceded them. Rochelle Ratner, who became ABR's managing editor, wrote

regularly for Margins, and I think my association with her

outlasted that with anyone else on the staff.

What I Wanted to Accomplish with the Symposiums

In addition to my having the opportunity to write whatever

I liked for Margins, and to commission all sorts of things from

other writers, I set up clusters of reviews and several reviews in

sequence through several issues.

But the most important opportunity the magazine offered me was a platform

for symposiums on contemporary poets. I had been thinking along similar

lines with Stations, and having Margins available further

stimulated my ideas in this area.

Something to bear in mind is that at this time the only series

even remotely resembling this was Berry Alpert's Vort, and a

"special issue" devoted to a given writer in just about any other

magazine consisted of three or four reviews and a photo. John Taggart

had done something similar to the symposiums in Maps, but that

magazine was long-gone when Margins started. The plethora of

special issues of the late 70s and early 80s came after Margins

folded, and was probably stimulated by

Margins and Vort. In the early 80s, Johnathan Williams

lamented contributing to Margins because everybody

asked him to contribute to their special issues and Festschrifts

during succeeding years.

At the same time, it's both amusing and sad to look back at my naivete

during my 20s, when I thought I'd always have Margins or something

like it available to me, and that I could continue working out criticism

from multiple points of view in all the extravagance Marry and the

Whitfords could finance. Perhaps even more so, I imagined a national lit

scene open enough to support pluralistic efforts by the time the web

made resumption of something like the symposiums affordable again.

My first impulse and coherent planning on the symposiums is simply an

extension of my thinking on triangulation, particularly its extension

into criticism. I had grown wary of the single voice of authoritarian

criticism before I started Stations, and thought that books should

inherently deserve more than one review. My view was, and still is, that

a solitary review of a book includes inherent falsification. Likewise, a

group of comments could not add up to some sort of absolute pronouncement.

But their variety could open up the work in ways that no single

review could. The symposiums could not only explore the works

considered from different points of view using varying methods, they

could also act as commentary on those viewpoints and methodologies

themselves. How much more or less do you get out of one approach

than another? Well, here was an empirical way to try that out through a

range of subjects and commentators. I had grown tired of what exponents

of various schools had labeled "fallacies." There should be nothing

absolute about an author's intentions, and it shouldn't be your sole

guide to understanding or evaluating what you read, but notions such

as "the intentional fallacy" seemed not only nonsensical, but part

of a priestly cast of critics who claimed the right to arbitrate and

unfold all significance, leaving the poets as something like test

animals used to determine what kind of warnings should be placed on

labels of consumer goods.

That priestly cast had been what The New Criticism had been about, and

seemed to be sneaking back, even into the alternative publishing scene. It

seemed fine to me to include some crit by people who did not write poetry,

but the majority of it should be done by practicing artists. They

knew more intimately what they were talking about, and did so from the

point of view of active participation.

All sorts of people constantly complained about the obscurity of

contemporary poetry. Of course, this didn't mean they paid any more

attention to a completely unobscure poet such as Charles Reznikoff

than they did to Louis Zukofsky, but it did seem that there should be

different ways to bridge the gap between artist and audience through

self or peer assistance. If the writers had more practice in explaining

themselves it might help audiences and artists understand each other

better. I had hopes that having the opportunity to create a body of their

own criticism, a vocabulary of their own, and a methodology not divorced

from the arts practiced, that the critics might not only explicate their

fellows, they would also tend to provide insights into their own work as

well. Eventually, I hoped that some of the commentators and guest

editors would come to be focal points of some of the symposiums in

the future. The reviewers themselves should be as much

the "subject" of a review as the work written about, and the milieu

and readership of the work should be as much part of the condition

of reading as the reviewer and author. I didn't like the terminology

or many of the ideas coming from semiotics and other critical methods

gaining ascendancy at the time - hence I simply liked to say, and still

prefer to put it, that traditional concepts of subject, object, and

referentiality needed to reconfigure themselves through variations

in practice.

As I proceeded with the symposiums, I noted that contributors tended

to take a less reserved approach than they might if they were

writing for, say Paris Review or The New York Times Book

Review. This seemed something to encourage. At the same time,

it made another possibility more appealing. By the time I got

the first couple issues out, my long-range goal was to create a

a series that could be revised and sold as a package to a main stream

publisher. Twaine was the first that came to mind, though others seemed

feasible. Selling a series of, say, 50 symposiums as

a set of books could have several advantages in addition to those

most immediately apparent. If the contributors had at times been rather

casual with the drafts they supplied for Margins, they might

be less so in revising them for publication in books. If some did and

some didn't, it would simply increase the diversity of approach in each.

With classic Syndicalism in the back of my mind, it also seemed likely

that if I could sell the series as a package, if poets d, m, and x

hadn't done very well in reputation and prestige, they'd still

be part of the package, and couldn't be dumped. At least I'd have more

to bargain with in keeping them in if the rest of the group had

done well enough. Thus, in addition to the other benefits of the series,

I also saw it as a rough draft of a set of books on later 20th

century American poetry with no orientation toward clique or school

or any other bias, except for the richness, experimentation, and

diversity of the era.

The First Symposiums

I would not have wanted the series to be tied into editorial conformity

any more than I'd want cookie cutter contributions. Hence it seemed best

that I should edit one in five myself and invite guest editors for the

rest. I initially had a bit of trouble selling Tom on the idea of giving

each editor as close to complete autonomy as possible. We did agree to

set a size limit and to avoid anything that would cause technical

problems. We also set bounds to fall back on in case something went awry

in ways that we could not predict. If an editor decided to turn a

symposium into a screed against a magazine or gallery which had rejected

him, or if it became a personal vendetta against an individual,

or a tool in romancing the subject, or a polemic which

ignored the nature of the poet, or anything else that ran outside the

reasonable bounds of symposiums on contemporary poets, we did retain the

right to pull the plug, assign a new editor, declare a moratorium until

the editor went through treatment or detox or whatever might be

necessary. Other than that, I gave each editor a completely free hand in

editing.

Despite the freedom offered, I wanted to make sure that nothing would

go too far wrong with the initial entries, in part to establish their

validity with their readership, in part to set a standard for those

that would follow. I also wanted to establish two things early if I

could: 1. credibility as to seriousness of purpose and method, and

2. a broad-based readership. Realizing that some symposiums would

get strange on their own and that some should stress heterodoxy - and that

all were coming out of the counter-culture of the day, it seemed wise

to begin the series with an unimpeachable subject, and a completely trusted

editor. This worked out as a symposium on Guy Davenport, edited by John

Shannon.

There was a bit of a wink in my decision to lead

with Davenport. Dick Higgins and I discussed a somewhat similar project

a decade later which may explain this. We decided that we should

produce a Festschrift in a stringently scholarly manner on the work of

Walter Savage Landor. All entries would be full dress, observing whatever

rules the MLA stylesheet consecrated. But all would be written by

people who had gained a reputation as extreme eccentrics, as far

outside the academic mainstream as possible. This was pure fun, but

it did refer back to Dick's amusement with my opening move in the

symposium series as well as our mutual enthusiasm for Landor.

Davenport, for me, however, was not just a respected scholar. He was one

of the most devoted polymaths on the scene at the time, and whatever else

was going on in that first issue, I did want it to focus on a

Renaissance man, as much at home painting as writing as translating.

He should have connections with a complete spectrum of contemporary

poets, and it didn't hurt that he had been corresponding with

Michael McClure during Michael's most rebellious phase, knowing that

Michael would be the subject of one of the symposiums. Davenport

had translated Greek classics, written avant-garde poetry, championed

conservative and radical poets alike. He knew his Homer and Dante, but

could study and discuss the arts of the Russian revolution just as easily.

He had had a strong impact on me, and I assume had been as open to

correspondence with other young people as lost in lunacy as I was when I

first began writing to him. His proteges had included Ronald Johnson

(potential subject for a future symposium) and Stan Brakhage, and I had

hopes that others of their range might be forthcoming from the strangely

creative area around Lexington, Kentucky - home at times not only of

Davenport, Johnson, and Brakhage, but also of Gerrald Jannecek,

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, and Thomas Merton. Ernesto Cardinal had

been a novice in the latter's monastery, and it was as Merton's student that

he was introduced to the poetry of Ezra Pound. There was no way I could

have known that this would lead to the comic but effective use of Pound's

ideas of imagism in the workers' writing programs of Sandinist Nicaragua,

but this was precisely the kind of extension of possibilities and connections

I wanted to see reflected in the further activities of the participants

in the symposium series. As much as Davenport was open to new approaches

in the arts, he was also an arch commentator on any subject that

happened to come before him, and hence something like a model

writer for symposiums like the one focused on him.

The second planned symposium was on Diane Wakoski, then at the

height of her power, and as popular a figure as a serious poet could be.

My hunch in the latter regard proved right when the entire print run

sold out almost immediately. Okay: this should fulfill goal two: if the

first symposium suggested that this wasn't going to be a series of infantile

gushy fan zines for someone like Charles Bukowski, the second reached out

to a broad audience without any kind of elitist aura. That it was edited by

Toby Olson, one of the figures who had read with her in the coffee houses

in lower Manhattan during the previous decade, when live readings had

achieved their most creative and transformative dynamics, in a scene that

either joined or ignored cliques, made this symposium more important to me.

As with John, Toby was an editor whom I could trust completely.

The scheduling of this symposium, however, was one of those best laid plans

of mice and men, not being completed until after two more installments

appeared.

I had tried some small variations on the symposium approach before

this, but it seemed a particularly good time to try it on Assembling

magazine. Assembling was completely unedited, something like a

magazine application of mail art. The restrictions on contributors were

that they could include no more than three leaves each and that they would

have to produce the leaves themselves and send them to Richard to be

assembled and distributed. For this gathering, I sent invitations out

to all those who had contributed to the last issue. The participants in

this gathering included quite a few who would become prominent later.

Kostelanetz extended the symposium when he

reprinted it in Assembling Assembling, an anthology of

Assembling related work.

If Davenport and Wakoski seemed ideal for openers, Rochelle Owens

and Michael McClure seemed important as figures to present early on in

what I hoped would be the body of the series. Curiously, these poets

shared characteristics that definitely did not come from a common literary

antecedent. The mid 70s was a time when poetry readings thrived, and

sound poetry was making a rapid ascendancy. Rochelle and Michael had

been central to the aural poetry of the previous epoch.

Michael had been part of the original Beat scene on the west coast, often

reading to jazz accompaniment, and almost invariably to poets who saw

public readings as the central sacrament of their movement. Michael

continued to read to musical accompaniment after the San Francisco Bay

scene turned venal. Rochelle had held forth voluminously in the coffee

houses and bars on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the early 60s,

which picked up some energy from Michael’s North Beach scene, but

also brought in influences from Black Mountain College, the poses of

what was called the New York School, the cool suavity of FLuxus, and also

the raw energy of that city in its post-war bragadoccio and the fact

that lower Manhattan was more thoroughly crammed with artists of all

sorts in the most feverishly inventive and hyperactively cross-breeding

frenzy the world had ever known.

The intensely oral nature of the poetry of each seems to have lead in

parallel directions. In one set of parallels, both wrote plays that pushed

the boundaries of what could be done with a scripted play about as far as

possible. This was at a time when Happenings and other forms of lightly

or completely unscripted performance seemed in the process of leaving

traditional theater behind. I wondered (quite mistakenly, as I see now) if

they were the last poets in the great tradition of English language drama,

poised on the edge of a completely new dispensation.

At about the same time, both had worked with complete abstraction,

without contact with each other, without knowledge of precedents in the

Zaum movement, and with, at most, only the briefest anecdotal

acquaintance with Hugo Ball and other Dadaists. Why they should share

this distinction among American poets, I don't know. It was important to

me, however, and my hunch was that it came from scenes in which

public readings played an essential role.

I edited the original Margins symposium on Rochelle Owens in

a state of what now seems wild optimism. Rochelle began publishing at

the beginning of the 60s, writing some of the most highly experimental

poetry of the time, and doing so in perhaps the most ferociously

misogynist literary milieu of the century, without a trace of any sort of

women's network or support group behind her. This was a time when

women were exhorted to leave their wretched roles as

housewives and aspire to the great libaratory condition of being a poet's

bread-winner and muse, but go no further than that. Except when

performing sexual services, they were supposed to keep their mouths

firmly shut. A literary hero like William Burroughs could even turn the

shooting of a wife into his most important career move. By the mid 70s,

feminism was in full flower, and language poetry, which Rochelle's

early work had foreshadowed by more than a decade, was in its formative

period. Rochelle had moved into a phase in which personae, mythic

archetypes, and strains of Judaic mysticism played a strong role in her

poems, and the dramatic character, latent in the dynamic readings of her

early work, had evolved into the writing of plays. Voices had always

been crucial in Rochelle's poems and plays on many levels. In the most

abstract early poems, the coloration of voice, sometimes taking slurred

speech as it base, sometimes finding its origins in the first stirrings of

anger or joy, sometimes feeling out the strange edges of irrational parataxis,

could modulate on the page through an intuitive process that has little if any

precedent in any previous poetry I'm aware of. This could further morph

into an almost coldly mechanical deadpan in works that suggested

automatic writing. When Rochelle moved on to the personae poems, the

changes of voice could turn in mid word or mid phrase, so that

individual works should not be considered as persona but as

personae poems - poems in which the mask changes as the

voice modulates. At times, there also seemed possibilities for a synthesis

of some forms of visual poetry in her work. My hope had been that she

could act as a central figure in an integration of some of the disparate

trends of the time - that she was, as Jane Augustine put it in her essay on

Rochelle in the symposium, a prophet. Certainly prophecies in her early

work were being fulfilled in the work of others as the symposium came

together. But the great synthesis I had hoped for in the 70s didn't

happen. Where would we be now if such a synthesis had taken place? Well,

that's a legion of opportunities missed, and something an aging poet can

look back on with a bit of sadness, but that's mere personal speculation.

As one of the two most completely and rawly inventive poet of the second half

of the century (the other being Jackson Mac Low), Rochelle

was the center of gravity for what I thought of as my first tier of

symposiums. This one I emphatically wanted to edit myself.

Click

here to go to Rochelle Owens's home page, which includes parts of

the symposium, and updates on it.

Michael McClure's symposium seemed equally important in that it was,

from my point of view at least, blatantly proscriptive, and I arranged for

it in a state of wild-eyed optimism similar to Rochelle's. If I didn't edit it

myself, I at least wanted to make particularly sure it would be done by

someone I could trust completely. Fellow Margins editor John

Jacob seemed precisely right. In fact, as an odd but perhaps instructive

coincidence, he had been thinking of doing something like this before I

asked him to edit the symposium.

From the time Michael had acted as one of the founders of the Beat

movement, he always retained a mercurial character. He could write

poetry as the roars of animals, but those roars often came forward in his

oral delivery with a surprising gentleness and delicacy, which could

modulate into other tonalities. Although his “beastspeak” might come

across to some as “primitivism” driven to its most extreme, Michael also

had a firm base as a biologist, thoroughly conversant in the science of

the time. On one level, it was something of a coup to include in the

symposium an essay on his poetry by Francis Crick, Nobel Laureate for

his role as co-discoverer of the structure of DNA. To me this represented

something that poetry should maintain, a strong tie with those who

explored what we are through the disciplines of science, and the

practitioners of poetry and biology should see the confluence between

each other’s labors. Michael could hang out with Hell’s Angels and go

through periods of extended altered consciousness by use of

hallucinogens, but he could also be a completely suave and witty writer

of plays that drew on resources as diverse as Renaissance masques, ritual

drama, existentialism, and the theater of the absurd. Not only could he

relate to scientists but also to rock musicians, writing lyrics for some,

including a favorite of mine, Janis Jopplin’s “Oh Lord won’t you buy me

a Mercedes Benz.” Most important to me, and I think a major factor in

his ability to move from one artistic milieu to another, is what I think of

as “Orphic” lyricism. No one in the Beat dispensation could bring the

delight in immediate perception and sensation to a level of complete

articulation as well as Michael. In the mid 70s, I felt that this kind of

lyricism was being submerged by the dull drone of workshop poetry

swamping the scene at the time. To me, he remains the central lyricist of

the second half of the century. If poets want to exalt the personal,

Michael’s ex-stasis seemed a better model than the endless sexual

bragging and personal whining that dominated large swaths of the poetry

scene, and still do today.

Click here to go to Michael McClure's home page, which includes

portions of the symposium and updates on it.

Planned Symposiums and the End of Margins

By the autumn of 1976, I had finished the first round of symposiums, seen

them published, and had several more in the works. Of those that were

published elsewhere, see Margins Symposiums, Part 2. By this time, the

magazine and Tom's family had become strained. Tom was unable to get one

of the finished symposiums out according to any kind of schedule, and was

unsure how to handle finances and editorial problems. He spent a good

deal of time talking and writing about this after the magazine folded.

These stories are (or were) his to tell. Some rancor remained on the

parts of some people involved, and Tom's inability to recognize the

contributions of his staff still has some Margins editors annoyed

or disgusted to this day. Although lack of credit where it is due is a

common enough phenomenon (perhaps we could call it an epidemic), Tom,

on the credit side, didn't cast any blame for the magazine's collapse on

anyone.