Since 1976, my focus has been on a range of visual and spatial

poetries with differing and shared concerns. Derivation, including

incorporation of previously used and extant materials, as well as

the investigation of and expansion upon visual poetries of other

writers dedicated to the visual page, and a poetics generally

insistent upon practical utility and function, has guided much of

this work.

While much of what's discussed and investigated over these

several pages concerns projects and strategies that I pursued during

the closing decades of the Twentieth Century, the work's impact

and potential for emerging poets and artists working in digital

formats is sweeping and unmistakable. Visual literacy and its

practice are of increasing cultural interest and adaptation. With

each year its purposeful application expands. There's much to be

learned for coming generations in the following discussion.

*

Active as a mail artist in the dynamic worldwide network,

around 1976, while living on North Lincoln Avenue in Chicago, I

coined the word poeMvelope. Behind the term was the

concept of rubberstamping poems on the flap side of envelopes to

make what was a functional physical object, mailable

internationally, impressionistic, often lyrical of language, kinetic in

arrangement and composition, poetic in lexical cosmology.

Interested in the physical textures of type, ink and paper and

motivated by a political poetics that celebrated and respected utility

and usefulness, conceiving and composing a visually tactical poem

on an envelope proved a fortuitous and durable artistic act. And,

quite specifically, I developed poeMvelopes out of

practical need, having moved several times over a few years. In

this pre-email era, I preferred to stay in contact with my network of

friends, poets and editors by correspondence as opposed to

telephone. I wrote many letters, not infrequently a dozen or more a

day, and many of my letters included (and were frequently built

around) poems—drafts seeking feedback, submissions, editorial

exchange, and letterpoems to friends who were practicing poets

and writers.

Using a Justrite Office Rubberstamp set and a single black ink

pad, my practice was to set from one to four rows of rubber type

and stamp on the verso of four envelopes (the desktop blotter pad

that I worked on providing surface area to arrange up to this

number of envelopes) these poems of four or fewer lines. As I

worked I often had theoretical, formal or erotic objectives that

invariably included attentiveness to visuality of impression and

certain criteria of visual poetics. My interest extended subjectively

in that I also sought to anticipate the receipt of the

poeMvelope by the addressee and I wanted to produce a

wrapper that would move, delight or in some way have an impact

on the recipient. And, I enjoyed, indeed I marveled at, the

suddenness of visual poetry's presentation of itself as I accepted or

initiated opportunities of correspondence.

Before the end of The Cold War and prior to the "information

revolution," Mail Art was a network of edgy and frequently

politically outspoken artists and the making and mailing of

poeMvelopes constituted critical and even dangerous

activity. Mail censorship was not uncommon, even in countries

that one might presume to be dedicated to free expression and

unfettered correspondence. The daily post was a moment of arrival

and what arrived was unannounced. Even now, the intimacy and

discovery of meaning in the personal letter enveloped in its own

wrapper carries an implicit message of singular meaning, of

uniqueness of intent, a manner of action initiated from elsewhere to

one's home, mailbox, hands and fingers as the words reveal

themselves and accumulate. Today, when the very existence of a

unified global postal system is threatened by the speed, minimal

cost and economies of digital transmissions, it is easy to lose sight

of personal mail's significance and desire. Some of Mail Art's

inherent qualities require a sensitivity to the postal system's

political, uniquely systemic global values, for example: convicts'

numerical I.D.; samiszat circulation; the word's actual resiliency,

perpetuity and power; uniform codes of stamps, weights and

measures; and perhaps most importantly, the reality that

handwritten messages were carried essentially from one hand to

another's somewhere on the ultimate planet, making it past all the

censors and barriers that interrupted unrestricted expression - those

that were and those that are. For me, poeMvelopes

expanded the poem internationally while avoiding all hierarchies

and barriers of editorship. And, they enabled me to concretize

poetry by the envelope's relatively confined surface requiring

concentrated and essentially minimalist strategies of language.

PoeMvelopes, and the wider range of mail art in a

complexly cross-medial way, investigate public/private expression

and exhibition, constituting a kind of mute and disembodied

performance. In this fuller context, poeMvelopes examine the

common denominators of the planet's written codes and groove on

letteristic wiggling of form.

Mail art, with its tacit bylaws of universal artistic democracy

and quest for a borderless and post-national language, offered an

alternative creative universe for visual artists disinterested in or

excluded from galleries and juried exhibition. Mail art provided an

option to literary publication and was an available, subtle extension

of what I practiced as a poet and correspondent.

Drawing on language bits from my pocket notebooks, I'd

develop the look and arrangement of the letters by inky rubber

stamp noodling. Thinking more in letters than in words or ideas, I

consciously built what might become a word from an initial mark

or letter. In the studio I'd make an edition run of eight to twenty

rubberstamped poeMvelopes, all but a few (which were

kept as artist's proofs and archival copies) subsequently addressed,

posted and released into that preemail grid of worldwide postal

codes, box numbers and addresses to engage remote and actual or

pseudonymous public/private politics, emotions and artistic

motives.

In AD 2001, correspondence in general and Mail Art in

particular rely upon different technologies and webs of connection

than was the case not long before the millennial pivot. That's

another discussion. Click here for reduced images of

poeMvelopes

These poeMvelopes were quickly made on a laptop

easel while on a mail art drive through northwest Ohio in 1983. I

packed a compact car kit of rubberstamp type and forms, several

inkpads, envelopes, postcards and postage. My spouse, Cynthia,

drove. I kept notes and stamped, keeping my senses and

imagination alert to opportunities and images as we stopped in the

agricultural region's towns and along rural roads. I'd do a set of

four, the number of envelopes I could fit on the board while

retaining room for a few rubberstamp letters and an ink pad or two.

As we came to post offices in the various communities I'd mail off

fresh pieces to regular correspondents, mail artists and upcoming

exhibitions. The work above is gestural, immediate in its active

connection to time and place and produced while the car was in

motion.

*

During the 1980's I edited three concept periodicals,

Bagazine, The Sleeze Art News (SANS),

and 11x30. I approached these fraglit editions as blending

time-capsule reportage, infobites and newsletter gossip with my

interest in unique editions and obsolete books, ephemeral

language, fragments, scraps and bits (hence, "fraglit," fragments of

literature), fugitive inks, discarded waste papers and founds—all

manifestations of periodicity. The Sleeze Art News was

textual in parodic approximation of a newspaper and laid out in

ways that drew on the visuality and immediacy of a noisy front

page.

Bagazine was less systematic, more loose-leaf and

generally filled an envelope, poeMvelope or some other mailable

bag with whatever materials I was involved with at the time -

photostrips or contact sheets, aged paper gone to dust, cutups,

drafts of poems, recycled junk mail, language concepts. The idea

for Bagazine arose after a trip to a Detroit envelope

factory where I was introduced to the vocabulary and industrial

process of that niche of the paper industry. A certain kind of cheap

die-cut envelope is known in the trade as a "bag."

Each edition of The Sleeze Art News was a unique

product. One representative example includes eight paper items in

addition to a 5&1/2 by 4&1/2 inch wrapper on which my typed

newsprint note reads in full: Note//some of a larger group of postcards

designed & executed while traveling across Ohio & based on familiar &

impressionistic signs. ALSO CONTAINS: 2 b/w reduced photocopies of

designs to appear in forthcoming ASSEMBLING (ed. Richard Kostelanetz).

Submissions asked to respond to the question: IF YOU COULD APPLY FOR A

GRANT OF $500,000.00 WHAT PRECISELY WOULD YOU PROPOSE TO

DO?//& 2 postcards designed on data printout cards, one pink and one blue.

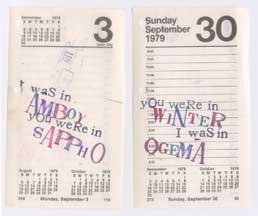

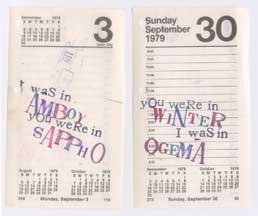

Above are two desk calendar pages from a prior calendar year.

The concrete idea is to set two lines of rubber type, one reading

"You were in" and the other reading "I was in," printing them in

varied sequence. Between these lines of text, and in eccentric (what

some font menus refer to as "San Francisco") type, I'd stamp

names of towns drawn from the road atlas—a travel exercise that

takes its particular pleasure from being conceived and made on-

the-roll. A visual suite of missed opportunities and bad timing

emerges from the three-dozen pages, which I arranged in pairs and

groupings like the two pages from this edition of (SANS).

These projects provided structures for a range of visual

language, much of it a graphic languagescape more expansive than

the lesser geography explored by visual poetry. Other Sleeze Art

News (SANS) and Bagazine inclusions and texts examined

typography and photography, catalogues, lists and an array of

paper ephemera. For example, using a portable ditto machine (yes,

the hand-cranked variety that relies upon smelly purple ink) and

carefully cut ditto masters, I printed out an edition of (SANS) on

the backs of canceled checks from the Toledo Bath House, a

longstanding neighborhood bath house that had recently closed.

Each complete issue ran about twenty pages, twenty checks. On

one side of the check was a text about cultural, literary, or local

history matters containing some personal reflection on public baths

in general and the Toledo Bath House in particular, while the other

side was a cancelled check made out ten to twenty years earlier to

some person or business, usually for small payments like $4.58 or

$23.50. The project was conspicuously voyeuristic and erotic. It

also was dependent upon and implicitly derived from a received

text, structurally challenging and engaging, tactile and very much

about things periodic.

Click here for a visual language cut-up

from an issue of Bagazine.

The third journalistic visual poetry project in the late 1980's

and early 1990's was the considerably more elegant and formal

offset periodical 11x30. 11x30, the title reflecting

the dimensions, in inches, of this broadside publication that I

edited and designed with the assistance of Sandy Koepke, staff

artist at the University of Toledo Publications Office, was

composed and printed using considerably higher production values

than either Bagazine or The Sleeze Art News.

11x30's production reflected Sandy's professional design

skills and featured paper stock that differed in color and ink from

issue to issue. It always included visual and lexical poetry by some

of my correspondents and friends, among them the poets Howard

McCord, Christy Sheffield Sanford, Michael Kasper, Bern Porter,

John Brandi, Paul Hoover, Geof Huth and Richard Kostelanetz,

and each issue also served as a flier announcing upcoming

performances and readings I'd booked in my capacity as Director

of the Toledo Poets Center. I had the printer punch a hole center-

top so the broadside could be neatly pinned up, kept and displayed.

11x30 was showy, of unusual proportions and provided an

excellent field for the publication of visual poetry, in that it

spaciously arrayed and distinctively printed visual and lexical texts

on a long sheet of high quality (though not archival) paper.

There was a mail art subset of values built into the editing and

production of 11x30. I had gradually become more

intrigued by personal networks of affection, friendship and taste,

and I consciously wanted 11x30 to demonstrate how so-

called "schools" or literary movements relied upon, though often

were reluctant to objectively admit, that they built their status and

excellence by recognizing and valuing literary, romantic and

personal affinities. By 1990 I'd sat on enough grant panels and

fellowship juries, read enough you-for-me-me-for-you jacket

blurbs, been to the requisite conferences, readings and confabs,

read the litmags and culture rags enough to recognize the

friendships that brought certain groups of writers together in

performance or print. Perhaps because I've enjoyed benefits as a

poet through the blended personal-and-anonymous network of mail

artists, I generally support and respect friendship as the basis for an

artistic project or inclusion, and while at its menial worst it yields

cronyism and schmoozy praise, when personal friendship

encourages the creative product of talented and otherwise

overlooked artists it offers an opportunity for exciting

breakthroughs, generosity and opportunities. I know where I stand

on this frequently contentious matter and as Toledo Poets Center

director I dispensed an annual presenting budget of four or five

thousand dollars a year, bringing in writers, poets and literary

ensembles that I valued or knew about and wanted to sponsor at

community venues. Friendship and artistic merit can be

intrinsically rewarding interconnected values.

11x30 used a poster format to announce upcoming

readings and present a glimpse of the poet's art, accompanied by

the work of other writers and artists I was in contact with and

whose work I respected and sought to promote. I viewed the

broadside as a chance to create a public for my interesting private

correspondence. 11x30 was rather widely and always

appreciatively reviewed. Poetry archives ordered it for their

collections and a number of individuals subscribed, though I'm

sure I was a less-than-reliable managing editor. Had 11x30

been a CD, it would have been considered a crossover product, as

it straddled that literary market line between ephemera and

archival. The issue announcing one year's performance of an

annual Jack Kerouac reader's theatre production, "Back To Jack,"

featured the full publication of Kerouac's "I Had A Slouch Hat

Too" and 11x30's premier issue republished d.a. levy's

"Tombstone As A Lonely Charm" along with two of levy's

concrete cut-ups in what I would argue is the finest presentation of

these texts to date. The wheaty papers and rich brown inks used for

these issues displayed the work clearly and with an antique tone

suitable to a broadside rendering of postmodern masters, each

prematurely dead.

Periodical literature is invasively nostalgic, instantly extending

into and inspiring memory. These projects all accepted and

noodled this emotional key. Perhaps, in my appreciation of the

opportunities nostalgia (and its deprecated partner, sentiment), I

reveal an inexact understanding of one of my graduate school

mentors, the late poet James Wright, a man quite masterful at

locating the opportunistic edge of memory and infusing nostalgic

recollection with bite, energy and depth.

*

As has been my practice for thirty years, I write poems lexical

and linear as well as those composed by actively plosive visual

strategies and concrete poetics. Spatial poetries, field poetics and

visual literatures iconic histories and prehistories are fundamental

to their reading and pleasures. Writing poems is habitual activity,

its requisite tools little but notebook and pen, and I always have

both in my pocket or pack. The typographic spatialities have

become gestural and almost go unscripted in my notebooks, with

breaks, white fields, lateral and vertical pauses and alignments

generally adjusted at the drafting table, typewriter or computer, all

of which I use along with pencil and pen. Though I briefly flirted

with one, I do not compose using a laptop. Elsewhere than in office

or studio I write by hand and use the arguably obsolete or

inefficient technologies of handwriting.

The pleasures of mark and smudge and the shaky legibilities of

my hasty cursive are more gratifying to compose than the crisp

registrations of keyboard and printer. The typewriter, so obviously

archaic and incapable of state-of-the-art visual specificities in a

digitized world, becomes obsoletely pertinent at this technological

juncture and the visual meaning of typed poetry is thus imbued

with fresh opportunities and replete with noir registries

and signification.

Brian Richards, publisher of Bloody Twin Press, in 1984

printed a lovely letterpress broadside of "My love is," a spatial

poem previously published in the journal of erotic poetry, Yellow

Silk, and subsequently in the Toledo Poets Center Press anthology,

Glass Will. During 1986, Richards invited me down to his

shop in the Ohio River town of Blue Creek to collaborate on the

typesetting and printing of unique covers for the subsequent

Bloody Twin Press edition of my small book of translitics,

Provocateur.

The tangible activities of holding type and setting it, damping

and pulling weighty rag sheets, the smell of ink and solvents -

these are sensual pleasures that have their impact on the patina and

patterning of visual poetry. Letterpress printers not infrequently

possess an appreciation and understanding of spatial and

typographically open field poetry well beyond that of writers

lacking the experience of the print shop. Many of the finest visual

poets and masters of the overall page have been practicing printers

and engravers.

Lester Dore, during a season of work in 1988 at Walter

Hamady's Perishable Press, set and printed a broadside edition of

my poem "What Do You Do With Mountains." Dore's

composition included his intricate geological rendering of

Wisconsin's unglaciated southwest as part of an expansively

conceived Ocooch Mountain Press bioregional packet. Alphabets

emerge from drawing. The cartographic clarities and symbolic

details of mapping, in this case Dore's cutaway sketches of

drumlins and moraines, echo certain prealphabetic signs, simplified

representations and repetitions of line. Tim Ely, in his several

artist's books exploring imaginary maps, inventive geographies

and gibberish gazettes, takes this relationship between spatial

language and the presumptive geographies of mapping to a

particularly interesting place.

The textures and impress of letterpress, with its almost Braille-

like code of fingertips and invitation to touch, adds measurably to

the language and referential relief of visual poetry. The codes and

history of gouge, smudge and scrim, of stylus mark, etch and

embraded rock is retained in the bite of the printer's press. In my

studio practice it is difficult to separate the use of materials derived

from letterpress printing from those designed for use as

rubberstamps. My visual poetry, as well as my studio environment,

mixes implements from both technologies.

And, specific to Dore's geological rendering of southwest

Wisconsin's landforms that shares space with "What Do You Do

With Mountains" on the softly textured paper he chose for the

broadside's printing, using language cartographically or in

gazettelike proximity to such artwork reaffirms the genesis of

writing in drawing, helpfully articulating the birth of letterforms in

the line's ascending and descending variations and extensions.

*

For an Ann Arbor gallery, calligrapher Susan Skarsgard created

a series of 30X48-inch ceiling hung, translucent Mylar panels of

my conventional linear poem "The Beautiful Letters." The

manifestations of physical language Skarsgard explored in her

calligraphic rendering were challenging to encounter. Her

calligraphy is freewheeling, at once both powerful and graceful of

stroke. She is an inventive, brave practitioner. Ambient light

filtered through five sculpturally hanging sheets on which she'd

enlarged and reduced portions of lines and words from the poem.

The background and foregrounded letters were of contrasting

frosted translucence.

While it is an extraordinary gift to have another artist locate her

possibilities in the visual and spatial suggestions of one's work,

Skarsgard's work posed for me the arch problem found in the

calligrapher's aesthetic presumption—that s/he can appropriate and

refabricate the shaping design and lyricism of another's text. This

is a large and complicated question for the entire arts community,

one driven by many interlocking technologies and cultural

assumptions which make the reuse (sampling, copying, versioning,

collaging, reprinting, etc.) of another artist's creative product

materially feasible and artistically interesting. It raises an

increasing range of issues for visual language artists.

"The Beautiful Letters" was originally dedicated to Skarsgard

after I heard her discuss her work during a slide/lecture at a

suburban Detroit library. This is important to understand and

respect, because visual poetries routinely draw upon and derive

from extant texts and available visual materials. Calligraphy has

historically represented, explored and exploited existing texts and

fields of language, transforming common print into "beautiful

letters." Visual poetry's ideas, tropes and imagery reside in the

physical letterforms and concretions that are also the poem's

words. A certain common impulse and perhaps parasitism unites

poetry and calligraphy.

I rebuilt language from Skarsgard's lecture and slide show,

which had previously lifted ideas, images and materials from its

sources. Bits of her words and the rhythms of her lecture's spoken

arrangements were appropriated by me, becoming part of the text

and texture of "The Beautiful Letters." She, next, reappropriated

my poem, a version of her earlier lecture and dedicated to her.

Skarsgard's responding version then became five translucent Mylar

sheets exhibited sculpturally and suspended from ceiling threads,

one sheet printed full text and the other four with enlarged details

of line clusters, words and letters, exquisitely designed and

professionally etched, lightly moving in the gallery air while

viewers walked around and between the artwork, those bits of what

had in a prior generation of artlife been the so-called poem "The

Beautiful Letters." And, in all, it was a memorable execution of

visual poetry, off the page while retaining the idea of the page,

surprising in its grace, calligraphic play and rhythm.

A subsequent project with Iowa City calligrapher Glen Epstein

never matured into a finished collaboration. Still, it was energizing

and exciting as a lesson in visual poetry, due to Epstein's wild,

splattery, freehand calligraphic style that stretches legibility

beyond alphabetically accessible reading. With Epstein's sprays of

ink and the movement of his letters into representational forms, a

wildly charged verbo-visual poetics of the total page begins to

emerge. Perhaps some day we'll complete the project.

*

During the early 1980's, I began to systematically examine,

research and make artist's books, an area of polyart and poetics I

only slowly was beginning to adequately understand. Supported by

a University of Toledo faculty felowship, I spent a summer in the

archive of the Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection of Modern

Illustrated Books under the knowledgeable and watchful eye of

Marilyn Syms, who at that time held the position of Curator of

Books, Prints and Photography at the Toledo Museum of Art.

Nuances of paper and structure, the achievements of visual and

lexical coordination and the zany freedom and obsessive passions

of artists' books increasingly attracted me in my studio and in work

that I brought into the university classroom. In this visual and

tactile book arts nirvana, I felt as if I'd been granted literary

citizenship in my own Fredonia, a niche state essentially ignored

by the bigshots and committees that canonized literary and poetic

merit. The materials I now kept fellowship with ranged across

genres, media and formalities. I better understood, or sought to

understand, that visuality, textuality and texture were co-

inhabitants and kin. And, artist's books were "priceless" after a

fashion that had long tweaked my interest, in that they were valued

from the lowest point of the price scale to cost's pinnacle—some of

the books had giveaway origins while others, such as those

published by the Arion Press, were supposedly high-end products

with extraordinarily expensive list prices.

For a variety of reasons rooted in what I perceived to be a

necessity to guard my privacy and creative subjectivities, I'd

generally avoided teaching visual poetry in the classroom. But

commencing in the late-1980's, I began to develop undergraduate

courses, first in Visual Language and then in Artist's Books. The

necessity of developing a syllabus and term's worth of lessons was

an opportunity to systematize the understandings about those

historical points and literary genres where visual art and writing

coalesced. Of course, I was looking back and across the long

history of writing, printing and literature at the very moment that

my students were growing up with the Internet and increasingly

fluent and inventive explorers of the expanding software programs

and creatively applicable Web technologies under their fingertips.

Robert Creeley, whose student I'd been at SUNY-Buffalo

during the early 1970's, collaborated with painters R.B. Kitaj and

Robert Indiana on significant artist's book editions of his poem

cycles A Day Book and Numbers. Viewing

Indiana's interleaved prints and reading the sequential poems of

Numbers in the German Graphis Press edition takes

Creeley's poems written in response to Indiana's ten paintings to

an elegant, visually signified level of meaning and recognition.

Reading the sexually aggrieved screeds of A Day Book in

an oversized, unpaginated, unbound folio where each daily sheet is

composed using a different typeface utterly rearranges and

reorients one's sense of this day-by-day poet's journal. All

elements of each edition add to its artistic quotient. The bookstore

trade's thoughtlessly standardized editions, when compared to

artist's books or livre' d'artistes, are such viciously industrial

products.

Courses I taught were cross-listed in the departments of Art

and English and the classes met at the University of Toledo's

Center for the Visual Arts, a beautiful Frank Gerhy designed

building attached to the Toledo Museum of Art, whose Stevens and

Bareiss book collections form an impressive archive and library of

historical and contemporary examples of the art of the book. The

University and Museum staffs were supportive and this enabled

classrooms to extend to galleries and special collections. Lessons

in the development of ancient scripts took the class to the

Antiquities Gallery, where etched bellies of Egyptian lapis scarab

pins, painted funerary objects and Grecian urns became a basis for

exercises and discussion. Medieval manuscripts were deeply

represented in the slide resource library and supplemented with

pages and texts from the archives. Periodically there was a

stimulating book exhibition on display. I constructed lessons

around examples of visual language, including such materials as

playing cards, game boards, Victorian type design, book jackets

and spines, cartoons, concrete poetry, livre' d'artiste and

contemporary artist's journals language fragments, inscription and

ritual objects. This process of course development cemented my

attention to the visual page and provided unique access and

proximity to a great museum's particularly pertinent collections.

I'd long been buying old books at estate sales and resale shops,

not as a bibliophile or collector, but to disassemble, cut-up and

subsequently print on with rubberstamps. I'd locate interesting

aspects of the page or elements of story that in different ways

inspired me. Having long made poeMvelopes, I'd

developed my interest in micro-narratives where one might suggest

a story in a few words, and I increasingly explored the intimate

suggestiveness of color and fragmentary or visually altered

language. I approached mail art and book art as proximate and

sympathetic genres of an artist's practice. Though it took awhile

for my ideas to clarify, I was working toward a theory positing that

personal mail and the posted letter functioned as the most intimate

form of the book, possessing the necessary criteria of unique

editions - paper, folding and cutting, wrappers, text, writer, reader

and so forth. In my studio I'd cut up books and overprint their

pages using rubber stamps, a few words to the page. I began

stamping geometric shapes, screens and representational images,

while keeping my work language-based and poetically

investigative.

Some of the long-term projects I've engaged are the open-

ended and unbound folios "The Origins of Poetry," "Gibberish

Entrees" and the political satire "Jesse Helms' Body." The Helms

series began during the Reagan-era culture wars when the National

Endowment for the Arts was the Senator's constant chosen target.

Derived from medical textbook illustrations and anatomical

cutaway drawings, "Jesse Helms' Body" begins with the premise

"…that upon his death, Jesse Helms' body is donated to art." The

work has been quite widely, but not inclusively, published. A San

Francisco exhibition in 1995 at Bill Gaglioni's Stamp Art Gallery

displayed the thirty-four pieces I'd at that time completed.

Gagliloni published an illustrated catalogue of the exhibition.

Working with artist's books clarified for me the intentions and

antecedents of visual poetry. Whether making my poems or

engaging the work of others, I now "read" as well as "look at"

visual literature. I'm less likely to be disoriented and confounded

by letters and words composed with visual and spatial strategies.

*

Visual poetry by masters of the genre such as William Blake,

Appolinaire, Kenneth Patchen, d.a.levy, Barry Nichol, Ian

Hamilton Findlay, Bern Porter or Emmett Williams is more easily

and broadly appreciated in today's visually and graphically

sophisticated culture than was the case as recently as a decade ago.

Such 1964 visual poetry projects as Walesse Ting's collaborative

artist's book 1 Cent Life or John Furnival's construction

"The Fall of the Tower of Babel," are, perhaps unfortunately, no

longer peripheral to language's recognizable literary conventions.

The graphic novel is now occasionally featured in the New York

Times Book Review.

Among my forthcoming projects and publications is a

collection to be published by Light & Dust Press that collects

many of the visual poems from the "Jesse Helms' Body," "Origins

of Poetry," and "Gibberish Entrees" folios. "Revisioning

Webster's," a lengthy series derived from dictionaries, along with

visual adaptations of pulp novels and romances will be included in

the Light & Dust edition.

Clearly, commodification with all its attendant hype and

compromise threatens the visual poet in a market-driven and

corporatized visual culture and it is cliché to

reiterate or paraphrase that which we all observe daily. Yet it is

important to note that developments change perceptions.

Worldwide familiarity with PC's, laptops, desktops, screen savers,

software programs, the products and manifestations of global

culture and a technologically-driven proliferation of actively

borderless fusion across all arts' categories to the point where such

a recently definitive term and once-helpful designation of "mixed

media" is preciously quaint and functionally obsolete,

paradoxically provides visual poetry particular opportunity. No

longer viewed as weird, illegible or poetically eccentric by a

culture that wears petroglyphs on t-shirts and paints by keystroke,

visual poets may well overcome artistic barriers that have long

limited audiences and marginalized serious consideration of their

work.

During March 1998 I spent a month driving around New

Mexico and west Texas. My objective was to encounter

pictographs and petroglyphs in their site-specific locations and,

armed with some books, maps and local directions, I'd park, then

hike back to private sites or along designated trails in public parks

through the region's pervasive landscape of pre- and post-

Columbian Anasazi, Mogollon or Chacoan ruins. Is it odd that I

could sense and feel the pre-alphabetic and embryonic presence of

language in the glyphic gouges, painted shards of pot and abraded

chips on the cliffs' faces, markers and stones, and on the smoke

smudged walls of caves?

Visual poetry is an ancient and powerful language act practiced

since prehistory. The marks of antiquity articulate with a luminous

power that continues through the work of history's anonymous and

named practitioners. The texts and designs of tomorrow's poets

will carry this long and articulate tradition into the future.